The Northern California Guides and Sportsmen’s Association (NCGASA) has filed a petition for regulatory change with the California Fish and Game Commission that would alter sport fishing such that only striped bass within a 10-inch size range could be legally harvested. Stripers less than 20 inches would be protected from harvest, as would stripers larger than 30 inches. The existing regulations allow anglers to keep any fish 18 inches or greater in length. The stated purpose of the proposed change to a “slot limit” is to contribute to the conservation of striped bass — to grow the population in the San Francisco Estuary and its tributary rivers and to boost its capacity for reproduction. NCGASA’s proposal to revise the regulations in order to increase the population of non-native striped bass in the Estuary is contrary to federal and state policy aimed at protecting native fish and should be rejected by the Commission.

One might expect that NCGASA’s proposed regulation change is motivated by a precipitous decline in the striped bass fishery, but the petition does not assert that angling opportunities for striped bass have diminished over time. In its silence on that issue, the NCGASA petition affirms what California Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) data show. The number of striped bass caught by anglers has increased over the last 30 years, while the hours devoted to angling have remained steady.

Acknowledging the trend of more striped bass being caught per unit time by anglers, an alternative justification for the petition could be that too many striped bass are being harvested. Not so — striped bass harvest has held steady since 1990 at about 50,000 fish per year. Moreover, the number of striped bass caught and released by anglers increased dramatically from 150,000 per year in 1990 to more than 250,000 per year in 2016, the last year for which data are available. DFW’s data suggest no immediate threat to the conservation of striped bass and no decline in angling success. If NCGASA disagrees about the quality of the angling experience, it did not say so, nor did it explain why in its petition that striped bass needs enhanced conservation attention.

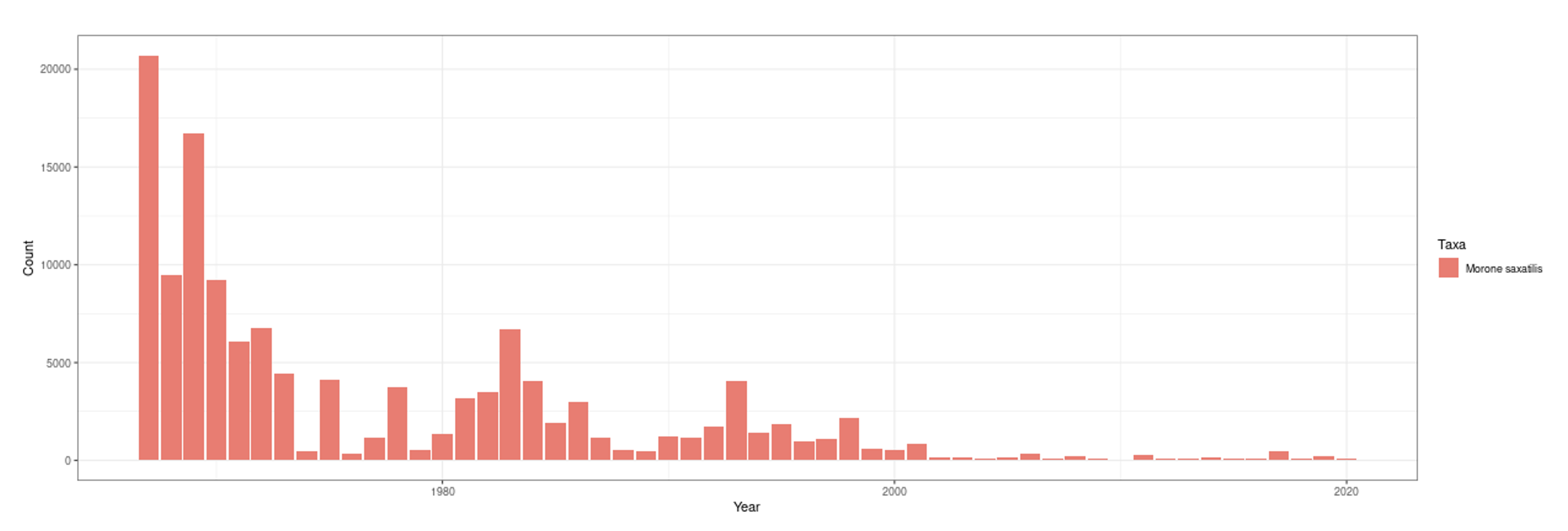

What NCGASA does offer to support its striped bass conservation measure is an observed decline of age-0 striped bass — the young-of-the-year — observed in the long-implemented Fall Midwater Trawl survey. Few young striped bass are captured in that general fish survey, but this is not a new development. Young striped bass in the Fall Midwater Trawl have been consistently low for the last 20 years (see the figure below).

Age-0 striped bass catch in the FMWT

If the abundance of young striped bass were indexed accurately by the Fall Midwater Trawl, surely a substantial decline in angler catch would be observable over that sampling period. DFW’s creel-survey data demonstrate the opposite pattern — anglers are catching more striped bass despite persistently low fall-survey returns. Biologists have known for some time that the Fall Midwater Trawl no longer functions as an abundance index for young striped bass and several other fishes of concern in the Estuary. The parsimonious explanation is that young striped bass, like a number of other estuary fishes, no longer rear in the open waters sampled by the Fall Midwater Trawl. Instead, young striped bass occupy near-shore habitats away from that trawl, where they are observed frequently in surveys that sample those areas.

The striped bass is native to the East Coast of the United States and was introduced in California beginning in the late nineteenth century. The species quickly adapted and flourished; soon thereafter the population in the Estuary and its tributaries supported a commercial fishery. The species is a highly prolific broadcast spawner, meaning that females broadcast hundreds of thousands of eggs or more in riverine circumstances. It is fast growing and migratory, characteristics help explain how striped bass came to be the apex predator on other fishes in the Estuary.

As recently as the 1990s, the Department of Fish and Wildlife stocked striped bass in the Estuary. However, because it consumes a wide range of fish species, including delta smelt and Chinook salmon and in light of the listing of these species under the federal Endangered Species Act in the early 1990s, DFW ultimately abandoned its stocking program.

Based on concern about the effects of striped bass predation on Chinook salmon and steelhead, the National Marine Fisheries Service asked the Fish and Game Commission to eliminate sport-fishing regulations that limit harvest of striped bass on two occasions in the early 2000s. On both occasions, the Commission refused to make any changes to the regulations. In 2008, the Coalition for a Sustainable Delta and other parties filed a lawsuit, alleging the Department was violating the federal Endangered Species Act by enforcing the striped bass sport-fishing regulations adopted by the Commission. Ultimately, the litigation was resolved by a consent decree. DFW, with support from the National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, subsequently recommended to the Commission a change in the regulations to increase harvest of striped bass. But the Commission rejected that recommendation from the federal and state wildlife agencies.

The fact that striped bass is an apex predator that has disrupted the native food webs in the Estuary is indisputable. A recent study found that native species comprise a great proportion of striped bass prey. An earlier study noted that “striped bass likely remains the most significant predator of Chinook salmon, Oncorhyncus tschawytscha… and threatened delta smelt, Hypomesus transpacificus.” In its Recovery Plan for Central Valley salmonids, the National Marine Fisheries Service recognized predation in the highest stressor category in its threat assessments for Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon, Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon, and Central Valley steelhead. Another recent article argues that striped bass controlled the delta smelt population in the Estuary going back decades.

The historical co-existence of abundant striped bass and abundant native fish species, including juvenile salmon and smelts, is often invoked to argue striped bass are not a threat to the Estuary’s protected species. Although data are lacking, any comfortable co-existence surely was short-lived. Moreover, the estuary and rivers tributary to it today are vastly different than they were when striped bass co-existed with more abundant populations of native species. The Estuary has undergone dramatic physical and ecological changes over the last 150 years. Those changes have fallen harder on native species — including smelts and salmonids — than on striped bass. At the same time, ecosystem and environmental changes have increased the potential for striped bass predation to adversely affect the viability of multiple native fish species.

Plainly, increasing the striped bass population in the Estuary by further restricting harvest of the species will increase predation on native fishes, including listed fish species. For that reason, adoption of the regulatory change proposed in the petition threatens to undermine efforts to protect native species. Should the Commission take such action, it would be actively undermining federal and state law and policy, in particular the federal and California Endangered Species Acts, which are expressly intended to conserve imperiled native species. Such action would also be inconsistent with the Commission’s Delta Fisheries Management Policy, which acknowledges fish protected under the federal and California Endangered Species Acts “have the highest priority.” As well, it would undermine the voluntary agreements that Governor Newsom has prioritized, which are premised on achieving viable native fish populations and include significant federal, state, and local agency resource commitments to do so.

Conjecture from some observers that if striped bass don’t prey upon and consume native fish, another piscivorous predator will do so, well, is just that – conjecture. That simple-minded counter argument does not provide a defensible basis for a regulatory change specifically designed to increase the population of a non-native apex predator in the estuary. If the State of California is committed to protecting its native wildlife and taking actions consistent with federal and state law and policy, the California Fish and Game Commission should reject the regulatory change sought by the petitioners.

No Comments